Choosing your project's dependencies

If you work on any non-trivial project, chances are you’ll install one or many external dependencies at some point. It’s a good decision to direct your limited resources at business-specific problems and use generic packages for boilerplate functionalities like sending emails, dealing with databases, parsing markup, etc.

However, you shouldn’t bring just any library in your codebase. While Packagist has, at the time of writing, around 60000 packages you could use in your project, most of them are not production quality.

Here’s a list of things to look for when choosing a generic library for a mission-critical project, in no particular order.

The library has a stable version

I take for granted that your software will go in production, that’s how it will bring value to your organization. I also suppose that you wait for your software to be stable before you launch it in the wild. You probably have several kinds of automated tests, and hopefully some QA to make sure you’re above a minimum quality/security threshold before code can be deployed.

You should hold external code to the same quality standard. That is, your project should only depend on stable libraries. By default, composer’s minimum-stability is stable, which is great, but it doesn’t mean you can’t mess up.

If you add a dependency with a "dev-master" or "0.3.*" version, you just pulled an unstable package. The maintainer(s) can change the API how they see fit since it’s implied by the version that it’s not production ready. There is no guarantee of backward compatibility between versions. Rafael Dohms has a nice article (cache) on his blog that explains how to select the version of a library.

Generally speaking, a package is considered stable if it has a version number that is at least 1.0.0. This version number brings us to my next point …

It follows Semantic Versioning

Following semver is not mandatory, and has less of an impact when you first install the dependency. However, it can have major consequences down the line when you decide to update your dependencies. With semver, the version numbers and the way they change can tell you how the code was modified from one version to the next.

From the http://semver.org/ webiste:

Given a version number MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH, increment the:

- MAJOR version when you make incompatible API changes,

- MINOR version when you add functionality in a backwards-compatible manner, and

- PATCH version when you make backwards-compatible bug fixes. Additional labels for pre-release and build metadata are available as extensions to the MAJOR.MINOR.PATCH format.

It basically means that, given a dependency that follows semver, if you update it from version 1.0 to 1.1, you can be pretty sure that there is no backwards-compatiblility breaks in its public API. This minor version bump means one or more features were added in a backwards-compatible way.

The “public API” part can be a bit of a misnomer. In PHP, every classes/interfaces from a package are public, and even though you can extend/implement any of them, it doesn’t mean you should. Apart from the “Composition over inheritance” principle, some classes in a package are not considered part of the public API.

For instance, take the HttpKernelInterface from the Symfony HttpKernel Component. This interface has an @api annotation, which tells you that it is part of the public API. You can safely implement the interface and provide your own HttpKernel implementation.

<?php

// ...

/**

* HttpKernelInterface handles a Request to convert it to a Response.

*

* @author Fabien Potencier <[email protected]>

*

* @api

*/

interface HttpKernelInterface

Now look at ClassMetadata from the Symfony Validator Component. Some class members are public to help with serialization, but are marked with the @internal annotation. You should not access these properties directly in your code because they can change from version to version. Event though they are public, they’re not part of the package’s public API.

<?php

// ...

class ClassMetadata extends ElementMetadata implements ClassMetadataInterface

{

/**

* @var string

*

* @internal This property is public in order to reduce the size of the

* class' serialized representation. Do not access it. Use

* {@link getClassName()} instead.

*/

public $name;

You should check each package to see if they follow semver before you depend on them. You should also check what is part of its public api before you extend the functionalities of a package. Some large projects like Symfony will document their backwards compatility strategy.

If a project has a change log, you can also get a sense of the semver-compliance by reading the changes between versions.

It is extensible

A generic package should have extension points that you can leverage to replace bits and pieces as needed. A vendor package may not fit your use case 100% out of the box, but if you can implement an interface and provide your own implementation where needed, then you don’t have to write your own generic library.

Look in the library code for extension points (e.g. interfaces, abstract classes, dependency injection) and look how the objects are created. Do they depend on concrete classes or abstract classes? Can you provide your own cache implementation? Can you write a simple adapter to use your homegrown yaml parser? That’s called the open/closed principle, and it states that a package should allow its behaviour to be extended without modifying its source code.

An extensible package will be much more flexible, and while you may need to write a bit of glue code to use it in your project, you will greatly benefit from it. The cheapest code is the one you don’t have to write and maintain.

It is active/maintained

While the word active may be subjective, it is one of the big selling point for me. The activity of a project will give you a rough idea of how fast features are added, and most importantly, how fast bugs are crushed by the maintainers.

Things to look for:

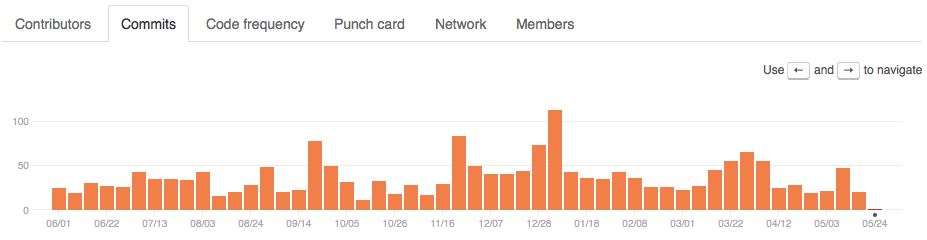

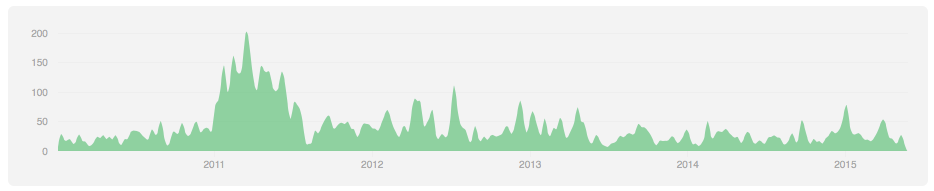

- How many commits? 10 commits doesn’t sound like a mature project.

- When was the last commit? Last year? Last week? 2 hours ago?

- How many contributors? Is it written by a lone developper? Is there a company backing the project? A whole community?

- How many open issues? A handful of issues is alright, but 100+? Scary.

- How long before an issue is fixed? Or at least, how long before maintainers responds to a new issue.

On github, you can look at the different graphs to get a bird’s eye view of the activity of a project.

Another thing I like to check is if other large or popular projects depend on it. There are two quick ways to do it that I know of. First, look at the number of downloads on Packagist. Most of them should be discarded if they don’t have at least a couple thousand downloads.

Second, you can search for the package on VersionEye and look at the number of references. You can click on that number and look for familiar names in the references, for instance: laravel, symfony, drupal, behat, doctrine, phpunit, phpspec, aws, thephpleague, etc. Chances are, if popular projects depend on it, it’s not going away anytime soon.

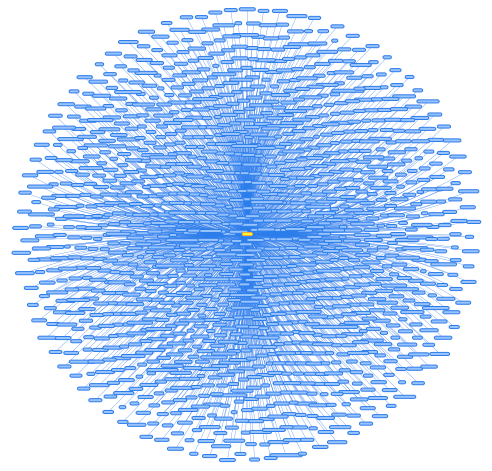

Update June 13, 2015: I couldn’t find the link at the time of writing, but a great tool to visualize the afferent dependencies of a library is The Packagist Graph. It is much faster than looking at a paginated list on VersionEye.

As you can see symfony/yaml is not going anywhere.

Update June 22, 2015: What you had to do on VersionEye, you can now do directly on Packagist!

It has a solid test suite

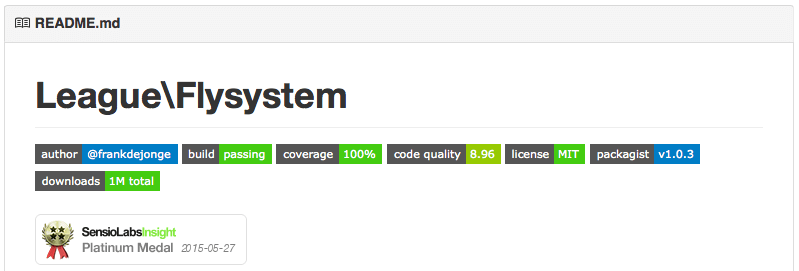

A solid test suite is a must, because you want a package that can prove it does what it says it does. Lucky for you, more and more projects now display badges on their GitHub page with metrics like code coverage, code quality, CI build status, etc.

For code coverage, I wouldn’t touch anything under 75% code coverage. When you think about it for a minute, it probably means that they didn’t write tests for the 25% of code that was really complicated and made testing difficult. That’s the part I would want covered in the first place, it’s a bug-hive. Also, open the phpunit.xml.dist file to see if anything was excluded from the coverage report, it’s possible to play with numbers. You may also want to search the codebase for @codeCoverageIgnore.

Two other interesting badges are the code quality badge from Scrutinizer and SensioLabsInsight. These tools can tell you how a library looks under the hood: the architecture, the patterns, the potential bugs, the security issues, etc. You can click on the badges to have more informations and make your decision. If you want to appreciate juste how hard it is to get a 10/10 on Scrutinizer or a platinum medal on SensioLabsInsight, try them on one of your small projects and watch as they tear it apart. Humbling experience.

The license permits the intended use

Important step, the software licence may or may not permit your intended use. Most open-source projects in the PHP eco-system opt for the MIT license, wich is very permissive. Some projects may use more restrictive licenses that limit commercial use. Search the license on tl;drLegal to have a summary in plain-english of what you can and can’t do with a library.

For example, with the MIT license, you can…

- use the work commercially.

- make changes to the work.

- distribute the compiled code and/or source.

- incorporate the work into something that has a more restrictive license.

- use the work for private use.

But you can’t…

- hold the author liable. The work is provided “as is”.

Also, you must…

- include the copyright notice in all copies or substantial uses of the work.

- include the license notice in all copies or substantial uses of the work.

It has quality documentation

I cannot state too strongly how important it is to have a thorough documentation at your disposal when using a generic library. It should explain in details how to use it, both with words and code examples. It should explain the steps required to install and bootstrap the package. Look at the docs, make sure your intended use is documented. Check if the extension points are documented, should you want to extend the functionalities.

There’s nothing more frustrating than having to figure out how to use a package by reading its source code because the maintainer couldn’t bother to write a minimum of documentation.

tl;dr

Before you add a new dependency to your project, make sure:

- it has a stable version available (

>= 1.0.0) - it follows semantic versioning

- it is extensible (open/closed principle)

- it is active and maintained

- it has a solid test suite

- its license permits your intended use

- it is well documented

If a generic package fulfills these requirements, you can be confident that it’s a good candidate. By strategicaly using external dependencies, you will save development time that you can spend on solving real business problems.

By the way, if you found a typo, please fork and edit this post. Thank you so much!